The article repeated and amplified remarks made in a January 10 speech by Chen Xiwen, the vice director of China's leading group on rural work. The Peoples Daily article was part of a series explaining the broader strategy of supply-side restructuring that China is pursuing in 2016.

Like the steel and housing sectors, China's grain production has overshot consumption, and a huge unsold inventory has piled up. Chen Xiwen said one of the priorities this year is to prevent this stockpile from growing even bigger.

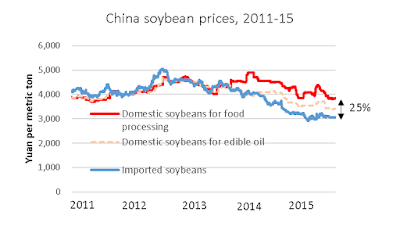

Different from steel and housing, China has tried to prop up domestic grain prices by limiting imports of grain and buying up surpluses to protect farmers' incomes. Chen Xiwen explained that China's grain prices are now far higher than prices in the international market. This is due to a policy of raising support prices to cover rising production costs, appreciation of the Chinese currency, and a decline in freight costs since 2009, said Chen.

The loophole in this price-support strategy is the lack of quotas to control imports of commodities that can substitute for corn. The substitutes include barley, sorghum, distillers grains, cassava, and cassava starch. Chen estimates that these substitutes displace about 50 million metric tons of domestic corn--about 20% of China's corn output, he said (this blogger calculates 22% of 2015 production of 224.5 mmt).

Calendar years. *2015 through November.

Substitutes=barley, sorghum, DDGS, cassava, cassava starch.

According to customs statistics through November, imports of corn and its substitutes for the calendar year were over 40 million metric tons, up from about 10 mmt in 2009 (the first year China began importing DDGS). The substitutes are omitted from most balance sheets. If they are added in, China's consumption of grain and related products for feed, starch, and alcohol production looks surprisingly robust over the past two years.

Chen says that holding domestic corn prices above the international price results in a confusing paradox in which grain production grew 12 years in a row, yet imports grew in parallel and grain inventories rose to a record level. He also notes that the production of corn doubled in 15 years while soybean imports grew to 81.7 mmt during 2015. Chen suggests that the increase in corn production overshot demand, and he suggests that corn production would be equal to demand if it were cut.

According to Chen, corn will be liberalized to let market supply and demand determine the price. The government will no longer be the main actor in the corn market--there will be diverse buyers and multiple distribution channels. Farmers need subsidies to ensure they receive reasonable income, Chen said, but the subsidies for farmers will be separated from the price. The government will give them a cash payment instead of holding the price at a high level.

A substantial decline in corn price has already occurred for many farmers, especially those in regions not covered by the temporary reserve price support program. Peoples Daily cites the example of a large-scale farmer in Shandong who received 1680 yuan/metric ton for her corn this year, down from 2100 yuan last year. Chen explains that the government has already reformed the price mechanism for soybeans, cotton, and rapeseed and is experimenting with target price subsidy payments to replace price supports.

While Chen said "everyone" agrees that the corn market must be liberalized, the timing and details of how it would occur are "complicated." Thus, there is no concrete announcement about when this would take place--will it be next month, in May, September, next year, or several years from now? No clues, leaving futures traders and other market participants exposed to a quantum change in corn price at the government's whim (and officials wonder why China's futures market is not used to set global prices...)

Chen and Peoples Daily revealed that they do not really trust markets. Market outcomes are great as long as they don't threaten China's "food security", reduce income of farmers, or result in domination of the market by foreigners. Officials have calculated that there is not enough grain traded in the world to meet China's needs if they were to import more. Therefore, Chen said rice and wheat will continue to have minimum prices since there can be no question of their production falling short of demand. Chen did not address smuggling of rice, the imbalances and distortions that would result when the price of corn falls to half the price of wheat, nor the plight of the rice- and wheat-milling industry which is unable to raise product prices to cover high raw material costs.

Rather than let farmers decide on their own to plant less corn as the price falls, the Ministry of Agriculture has concocted a giant plan to switch corn area to other crops in a "sickle"-shaped region extending from the frozen northeast through the parched northwest and into the mountainous southwest. The plan will begin this year. Officials are exploring land retirement and fallowing programs. Production costs will be reduced by cutting back on chemical fertilizer and pesticide use. Farms are expected to become more competitive by enlarging the scale of their operations, developing services for farmers, and improving seeds and other technologies.