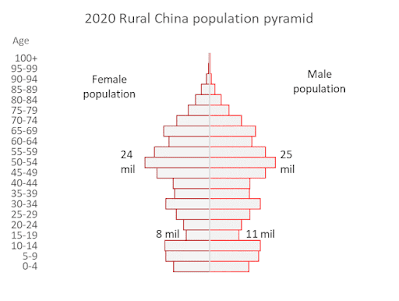

China's countryside is gradually turning into a warehouse for the country's aging population and the working-age population shrinks.

The "population pyramid" for China's countryside in 2020 has a hollowed-out base with relatively few people at peak working ages of 15-49. The largest cohort of rural people in 2020 were aged 50-54, with 24 million women and 25 million men in this age group. By contrast there were only 11 million males and 8 million females aged 15-19 in rural China during 2020.

|

| Calculated from China's 2020 population census. |

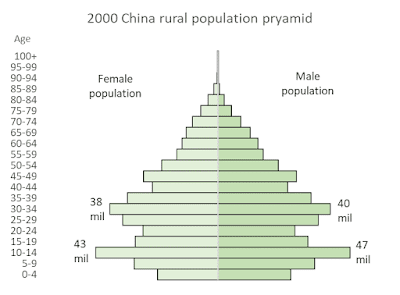

Back in 2000, the rural population pyramid had a thicker base of working age people. Folks age 50-54 in 2020 (a baby boom born in the late '60s to make up for the starvation after Mao's "great leap forward") were aged 30-34--at peak working age. There were so many rural people at working age then that underemployment in the countryside was a major concern in the early 2000s. That cohort was also at peak child-bearing years in 2000, and they had produced a baby boom "echo" of kids aged 10-14 in 2000. In the late 1990s it was urgent to get into the WTO in order to jump start the economy and create jobs to absorb the huge rural population. On the supply side, the seemingly bottomless supply of young rural people looking for jobs was a major factor that powered the fantastic growth of the Chinese economy during the first decade of the 2000s.

|

| Calculated from China's 2000 population census. |

WTO accession succeeded in solving the rural underemployment crisis, but it hollowed out the rural population structure, leaving mainly old folks and children behind.

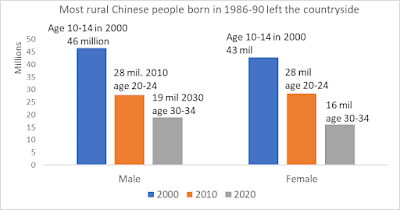

The big cohort of rural kids in 2000 disappeared from the rural population as they reached peak working age. In 2000 there were 46 million rural boys aged 10-14 years old. By 2010, these boys were men aged 20-24, and only 28 million members of this cohort were still living in the countryside. By 2020, this cohort was aged 30-34, and only 19 million were still in the countryside. Thus, only 40 percent of the 10-14-year-old boys from 2020 were still in the countryside twenty years later. The rest either migrated to urban jobs (or were lost through statistical inflation/deflation.) The number of females in that cohort dropped from 43 million to 16 million, a 63-percent drop.

|

| The chart follows the population of rural cohorts born during 1986-90 over China's censuses of 2000, 2010, and 2020. |

The consequence is the big hole in the rural population for folks at peak working ages in 2020. This is evident by overlaying the 2000 and 2020 population pyramids. The population of rural people at ages of 50 or more has grown from 157 million to 211 million over two decades while the population of working-age people ages 20-49 years old has fallen by half from 366 million to 181 million. The number of rural kids under age 20 has also plummeted from 261 million to 118 million.

The role of the countryside in the Chinese economy is now fundamentally changing. Traditionally, the countryside was a reservoir of labor that could be called forth to support booms and sent back to the countryside to return to subsistence farming during slow periods. Rural people were expected to farm and feed themselves with a small surplus to feed city people. Now the countryside is turning into a giant home for the aged. According to the 2020 census, 121 million people ages 65 and older lived in China's countryside--46 percent of China's elderly population.

China's cities have a lot of elderly people too, but the economic and fiscal divide between city and countryside presents a serious challenge for supporting the rural elderly. Many of the elderly still engage in subsistence farming but this cannot provide a satisfactory standard of living. Chinese agricultural leaders are desperate to mechanize and scale up farming as they watch the agricultural labor force age and shrink. Their vision is for aging subsistence farmers to become surreptitiously shoved off the land by making them shareholders in phony farm cooperatives that often generate little or no dividends.

It's going to get worse. Note that rural China had 35 million 10-to-14-year-olds in 2020, down from nearly 90 million in 2000. Most of those 35 million 10-14-year-olds will disappear from the rural population over the next two decades.

China's leaders have long relied on Confucian respect for the elderly and family ties to motivate working-age migrants to send remittances to their aged parents in villages on their own initiative. What happens when the informal remittance system breaks down as migrants become more accustomed to city life where citizens are told to rely on the government for support? It also breaks down when migrants lose their jobs, face astronomical living costs and school fees, or lose savings in real estate crashes and financial meltdowns.

A rudimentary old age and health insurance system has been set up in the countryside but the payments are much too small to provide a decent standard of living. Most of China's financial assets are in cities and there is no functioning mechanism to transfer funds to aging rural people. Rural government have no tax base to support rural elderly. Taxes on farmers were eliminated in the 2000s and now rural governments are responsible for handing out a growing menu of subsidies. They relied on selling off land for development projects to generate revenue but that golden goose has stopped laying eggs. Xi Jinping advocates creating agricultural industrial chains to bring prosperity to the countryside, but the dirty secret is that most of the value added in agricultural industrial chains is created in cities. Agricultural processing is a highly capital intensive industry that creates few jobs.