China will investigate impacts of imported beef on the Chinese industry to determine whether safeguard measures to protect the domestic beef industry from imports are justified, according to an announcement by the Ministry of Commerce on December 27.

China's national livestock industry association and 9 provincial associations submitted an 81-page application for the investigation that claims the increased volume of beef imports since 2019 has harmed the Chinese beef industry.

The Commerce Ministry's announcement cites a 64.93% increase in beef imports from 2019 to 2023 and an increase in imports' share of the Chinese beef market from 20.55% in 2019 to 30.9% in the first half of 2024 to justify the investigation. The announcement claims that "there is a causal relationship between the increase in import volume and serious damage to China's domestic industry.

An explanation of the investigation posted by The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs reports that two-thirds or more of farms have been incurring financial losses averaging 1000 yuan per cow for 8 months due to beef prices that are at their lowest point in 5 years. The article suggests that many farmers are heavily in debt, cows are being sent to slaughter, and some farms have quit the industry.

The investigation will examine imports of fresh, chilled, or frozen beef (HS codes 020110, 020120, 020130, 020210, 020220, 020230) between January 1, 2019 and June 30, 2024. The request lists 22 exporters in 11 countries and 15 Chinese importers to be investigated. The request claims that imported beef and domestic beef are comparable in quality and can be substituted for each other. The investigation will conducted from December 27, 2024 through June 30, 2025.

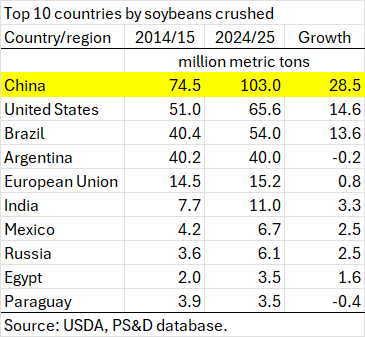

A law professor from China's National University of Politics explained to Peoples Daily that safeguard investigations are permitted by WTO rules to protect domestic industries from a surge of imports. A safeguard differs from anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations because it applies to imports from all sources and does not target a particular country. China's antidumping investigations have mainly targeted developed countries: U.S. broiler meat, distillers grains and sorghum; Australian barley and wine; and this year European Union pork and Canadian rapeseed. However, the proposed beef safeguard measures will mostly impact beef exporters in Brazil and elsewhere in Latin America where China is trying hard to make friends and expand its influence.

The request for the beef safeguard investigation shows over 40% of China's beef imports came from Brazil during 2023 and 2024. Fourteen of the 22 exporting companies identified for investigation are in Latin America: 4 each in Brazil and Argentina, 3 in Uruguay, and one each in Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico. The investigation list also includes 3 exporters in the U.S., 2 in Australia, and one each in Ireland, France and New Zealand.

Customs data show Brazil has been clearly the main source of the imported beef surge during the investigation period that begins in 2019. Argentina and Uruguay are the 2nd and 3rd-largest suppliers. Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, and Panama have also participated in the surge. Other Chinese friends Belarus, Russia, Ukraine, and Serbia have also contributed to the surge, but no exporters in those countries are targeted for investigation. China's imports of U.S. beef have rebounded during the investigation period but are comparatively small. Imports from Australia and New Zealand have been relatively stable. China banned beef from 10 Australian suppliers during 2020-22.

|

| Chinese customs data, HS codes 020110, 020120, 020130, 020210, 020220, 020230. |

The application for safeguard investigation claims that growth in beef import volume is "recent, sudden, sharp and significant," but China's beef imports have been growing for a decade. The request for investigation fails to recognize that the rising trend in beef imports stopped in 2023--it shows charts with trend lines drawn through data from 2019 to 2023, ignoring the end of the trend in 2023-24. A comparison of quarterly imports (chart below) shows no trend in imports since the second quarter of 2022. It's probably no coincidence that the flattening of import growth and decline in Chinese beef prices during 2022-24 corresponds to the tanking of the Chinese economy.

|

| Source: Chinese customs data. |

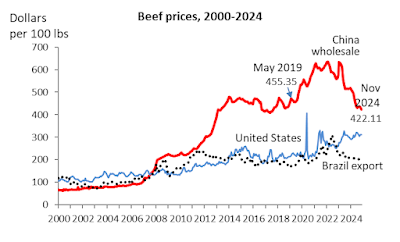

The request for investigation cherry-picks percentage changes in imports and Chinese beef prices to claim that surging imports caused China's beef prices. But beef prices in China actually grew and remained high during the fastest surge in beef imports in 2019-22. Chinese beef and cattle prices did not begin to fall until 2023 and 2024--after beef imports had stopped growing.

China's beef output expanded rapidly during the years of import growth. Official data show that China's cattle inventory grew 18% from 2018 to 2023, and the Ministry of Agriculture article admits that beef cattle inventory grew to a record high in June 2023. Beef output increased by 3.8% in 2021, 2.9% in 2022, and 4.8% in 2023. Production increased 4% year-on-year in the first half of 2024. Chinese producers appear to have expanded aggressively in response to the 30-percent Chinese beef price increase during 2019-20. Now the beef price bubble in China has popped.

|

| Source: China National Bureau of Statistics, agricultural product prices. |

Chinese beef prices diverged from international prices more than a decade ago, and Chinese domestic wholesale beef prices were often twice as high as U.S. and Brazilian prices over the past 10 years. Chinese beef prices did not begin their steep decline until 2023. The request for safeguards claims that a decrease in prices of imported beef caused the decline in Chinese price. Brazilian prices declined from a temporary peak in 2023 but there is no long-term trend in Brazilian beef prices. In the U.S. beef prices fluctuated and drifted upward, probably a main reason why the U.S. share of China's beef imports was less than 6% in 2023 and 2024.

|

| Sources: China Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, USDA, FAO. |

Beef prices are dropping toward parity with international prices, popping the Chinese beef price bubble that formed 5 years ago. This blog has pointed out several times that Chinese prices have been declining for many agricultural commodities over the past two years. More actions like this safeguard investigation will be rolled out as Chinese authorities get nervous about restive farmers, reversal of progress on rural poverty alleviation and undermining of the rural revitalization initiative.