China's Xinjiang "Autonomous" Region is the world's biggest cotton-producing region, but its cotton farms depend on billions of dollars in subsidies to keep them viable in what is also one of the world's most remote regions. Depressed cotton prices this year are inflating the subsidy bill, but officials grudgingly pay the tab to support this "pillar" industry, maintain stability on the fringes of the empire, and avoid relying on cotton imports from unfriendly countries.

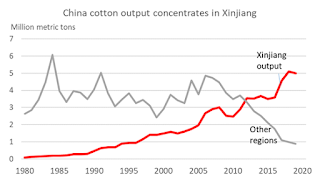

Rising wages generally spell trouble for production of cotton, one of the most labor-intensive field crops. China's farmers were eager to grow cotton when they were poor in the 1990s, but they have been quick to abandon the crop as wages grew. Cotton production fell in eastern and central regions, and increasingly concentrated in the Xinjiang region bordering central Asian countries where yields are higher, there are fewer alternative crops, and where the government was willing to spend on subsidies to pacify a region vulnerable to unrest.

Cotton production in China's "inland" (内地) regions fell from a peak of 5 million metric tons (mmt) in 2006 to under 1 mmt in 2019. Xinjiang's production grew from 3 mmt to 5 mmt over the same years. By 2019, Xinjiang accounted for 85 percent of China's cotton output, according to the country's National Bureau of Statistics. With China accounting for 22 percent of global output, a little arithmetic shows that Xinjiang produces 19 percent of the world's cotton, yet farmers say the crop is unviable in Xinjiang without generous subsidies.

|

| Source: Calculations using China National Bureau of Statistics data. |

|

| Xinjiang accounted for 85 percent of China's cotton output in 2019. |

In August, a Ministry of Commerce researcher wrote in China's Yicai business newspaper that cotton production must be preserved because cotton is a pillar industry in Xinjiang and plays a critical role in preserving social and economic stability. Excessive reliance on cotton imports, the researcher said, would leave China vulnerable to disruptions of import supplies from the United States and India (the two largest exporters). This year, in particular, the researcher said, China's cotton is under pressure from the covid pandemic, summer flooding in southeastern provinces, and U.S. sanctions.

Back in 2011, Chinese authorities tried to stanch the loss of cotton production by launching a "temporary reserve" price floor for cotton, but this proved disastrous. The government ended up buying most of the domestic harvest at the sky-high floor price while allowing textile manufacturers to import cheaper foreign cotton. After three years of piling up expensive cotton reserves, Chinese authorities ditched the floor-price and launched a 3-year trial "target price" subsidy for cotton in 2014. After a second 3-year trial authorities promised a new policy for 2020, but in March the National Development and Reform Commission announced that the target price policy will continue this year with minor tweaks.

The target price program allows the market price to be set by supply and demand. The government gives farmers a deficiency payment when the market price is less than a "target" price calculated to cover production costs plus a "reasonable" profit. The payment is based on the difference between the target and the average market price, thus the subsidy grows bigger as the market price falls. The target price subsidy was limited to farmers in Xinjiang. The payment is distributed to farmers in two tranches--one based on the area of land they plant and the second on the amount of cotton they sell. Xinhua news reported earlier this year that farmers and processors in Xinjiang clamored for continuation of the target price subsidy this year, and farmers insisted they could not cover their costs without it.

The target price subsidies were fat during the first two years of the program. The market price for cotton plummeted to about 25 percent below the target during the 2014 marketing season, and 33 percent below the target for 2015. Prices rebounded in 2016, but they were still about 15 percent below the target price. China does not reveal much about its cotton subsidies, but information in China's reports on farm subsidies filed with the WTO show the target price subsidies totaled:

- 2014: 28.7 billion yuan ($4.65 billion), equal to 22 percent of the crop's value that year.

- 2015: 28.0 billion yuan (27 percent of the crop's value--somehow they said the value of the crop went down 30 percent!)

- 2016: 15.4 billion yuan ($2.32 billion and 19 percent of crop value) when the market price rebounded.

|

| Source: China Ministry of Agriculture. |

The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps--an archipelago of army-run industrial and farming complexes strung across the region--surely benefits from access to credit from State-run banks, subsidies for machinery, R&D, and land reclamation. The Corps produced over 2 million metric tons of cotton in 2019, 41 percent of the Xinjiang total. The Corps' farms mechanization rate reportedly rose from 69 percent to 82 percent between 2015 and 2019.

Cotton farmers in nine "inland" central and eastern provinces also receive subsidies, but cotton output in those provinces nevertheless fell precipitously. An article in March this year criticized "inland" cotton subsidies for being announced and paid long after the crop was planted, and thus having weaker production incentives than those in Xinjiang. According to the article, the "inland" subsidy began at 2000 yuan per mt and in subsequent years was 60 percent of the Xinjiang subsidy. The article called for inland province subsidies comparable to those given in Xinjiang.

The geographic separation between cotton production into Xinjiang and textile manufacturing in provinces 2,000 miles to the east led to another layer of subsidies for cotton transportation. The subsidy began at 400 yuan per metric ton during 2011-14 and was raised to 500 yuan per metric ton in 2015. In 2016, the Xinjiang cotton transport subsidy was raised to 560-800 yuan, depending on staple length and region. China reported combined totals for transportation and seed subsidies in its WTO filings that indicate the transport subsidies are in the 1-to-2 billion yuan range annually. Adding in these subsidies brought China's total cotton subsidy burden to 24 percent of cotton output value in 2014, 29 percent in 2015, and 21 percent in 2016.

A 2019 post discussed a third layer of subsidies to support development of textile industry in Xinjiang. A plan in 2014 aimed to create 1 million textile industry jobs in Xinjiang by 2020.

Last month, China's food and commodity reserves bureau announced a plan to buy 500,000 metric tons of cotton for national reserves from December 1 to March 31 in an apparent move to bolster cotton prices and restock reserves. The purchase price will be adjusted weekly based on market prices, and reserve purchases will be suspended if the domestic price rises 800 yuan/mt above the international price. Futures prices and cash prices for Xinjiang farmers shot up around the National Day holiday due to vigorous demand. Supplies are tight outside Xinjiang due to continued decline in planted area and severe flooding in several cotton provinces. One cotton industry commentary thought the reserve purchase announcement would add to a rally in cotton prices. However, a good crop in Xinjiang due to good weather and a surge of late-harvested cotton helped dissipate the upward momentum in cotton prices. As of September the January 2021 futures contract price was 31 percent below the target price, but the October rally narrowed it to 21 percent. This year's subsidy payout may be reduced by $1-to-2 billion if the price rally can be sustained through the marketing season.

|

| Source: Zhengzhou commodity exchange. |

Lack of labor for cotton-picking is a longstanding problem for Xinjiang's cotton farms. According to the Commerce Ministry researcher writing in Yicai, each year 100,000 migrant workers are brought from other Chinese provinces to pick Xinjiang's cotton in September. Mechanization has reduced the need for these migrants (the machinery is also heavily subsidized), but last year a Xinhua article reported that every train arriving in Xinjiang's Aksu--the largest cotton-producing area--during September carried 4000-5000 workers from other parts of China arriving to pick cotton for two months. The prospect of bringing in a massive cotton-picking labor force became a concern when Xinjiang had a surge of covid cases during July and August.

A recent cotton industry analyst's survey of the Xinjiang harvest observed a noticeable acceleration in adoption of mechanical cotton harvesters motivated by the decline in migrant workers arriving this year--due to the pandemic--and the cost advantage of mechanical pickers. There was no mention of subsidies for the machines, but they surely were a factor. State-run news media were full of articles and videos about cotton-picking machines as harvest season arrived. (A video showing fields in Kashgar dotted with mechanically harvested bales last week available here; demonstration of equipment for Chinese farmers on State TV here does not show automated balers.) Industry data reported that 72 percent of the cotton had been picked as of October 23, five percentage points more than the same time a year earlier, so the pandemic has not slowed the cotton harvest.

Last week, 138 asymptomatic covid-19 cases were discovered in a single village factory on the outskirts of Kashgar in the western corner of Xinjiang. A lockdown has been put in place, air travel has been suspended, and extensive testing in the surrounding region is underway. Kashgar is one of the top three cotton-producing areas in Xinjiang. There is no indication whether these infections are linked to cotton-picking, but many warehouses in the Kashgar area suspended cotton purchases last week. Outsiders in Kashgar are not required to quarantine nor present nucleic acid test reports.

5 comments:

Such as useful information. I really like this blog posting site. Thanks for sharing it.

SMS Non Woven Fabric Manufacturer | Non Woven Fabric Supplier

Frozen Pork Front Feet for Sale<a href="https://pde-sur-limitada.com/es/product/frozen-pork-front-feet-for-sale/"https://pde-sur-limitada.com/es/product/frozen-pork-front-feet-for-sale/

Thank you for the informative blog. We provide Agriculture technology Development Services in India. Which play an important role in Providing Services at affordable prices Find our Services in detail.

The Canadian Experience Class (CEC) is a permanent immigration scheme for people who have worked in Canada for at least a year. It is a component of the Canadian experience class and expresses entry. Canadian Experience Class

Informative

Post a Comment