Reports of serious drought and pictures of parched fields have circulated on China's internet over the past two months. While Chinese officials acknowledge drought impacts, they insist the wheat crop now being harvested will be normal. We'll have to wait for market prices and imports to reveal whether drought has meaningful impact on China's supply of wheat--the main crop harvested during the summer months.

An April article on Chinese social media observed that many reports of serious drought bubbling up around the country conflicted with the agriculture ministry's pronouncement that a "strong foundation had been laid" for a bumper harvest of summer-harvested crops. At the same time, that article also observed that posts by online influencers in China may not be credible either since they have incentive to exaggerate drought problems to attract attention. Whom to believe? Will China resume large imports of wheat after cutting imports sharply last year?

In early May the Chinese communist party's Liaowang (Outlook) news weekly's "Beware of Continuing Drought in Grain Producing Area" warned that low rainfall since last fall that had stunted the growth of wheat plants across the country. Liaowang's reporter said that interviews conducted in Provinces of Jiangsu, Guangxi, Shaanxi, Henan, Hubei had revealed worsening drought conditions, infestations of pests and plant disease, and drinking water shortages affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

During the same week Shanghai-based news outlet The Paper described government activities in Jiangsu Province to mitigate drought resulting from 5 months of below-normal rainfall. The central Ministries of Finance and Agriculture allocated disaster prevention funds for 6 Provinces of Shanxi, Jiangsu, Anhui, Henan, Guangxi, and Shaanxi to irrigate crops and to spray growth-promoting chemicals, herbicides, fungicides and pesticides on the fields.

Xinjing Bao, another communist party outlet, reported in mid-May that rains had eased drought conditions in the southern part of Henan Province, but drought continued in western and northern parts of the Province. Agricultural officials promised funds for irrigation, but farmers in some parts of the province had given up and started harvesting their wheat about a month early. A China Agricultural University Professor declined to make a pronouncement on whether Henan's wheat output will decline this year.

An article posted May 20 reported a Shaanxi Province farmer's assessment that he expected a wheat yield 90-perent less than normal and complained that his corn seeds had not germinated.

China's weather service showed many areas with seriously low soil moisture on April 15. Rains eased drought in many areas by May 28, but it might have been too late to overcome impacts of the dry conditions during the key growing period for wheat kernel formation.

| Soil moisture April 15 | Soil moisture May 28 |

|

|

A May 28 article in State media claimed China had created 562 million tons of artificial rainfall to mitigate drought that has persisted across many parts of China since the beginning of this year and continues to impact farmers now.

Each official news media article dutifully reports plans to address drought conditions. However, irrigation is not possible in hilly areas and places where rivers have dried up. Liaowang reported that the water level was dangerously low in the Dujiangkou Reservoir that feeds the central route of China's massive south-to-north water transfer system. Water levels were measured at 2-meters below normal at 3 monitoring stations on the Yangtze River that supplies the water diversion project.

On May 20 an official in charge of grain reserves decreed that the summer grain situation is "overall normal" and the quality of the crop is "relatively good overall" despite lower-than-normal rainfall this year. The National Administration of Food and Commodity Reserves predicts that 85 million metric tons of wheat will be procured from the harvest that is beginning now. That would be up from 75 mmt procured in 2024, which was up from 68 mmt in 2023. On the same day a weather report in Farmers Daily advised wheat growers in western and northern Henan, southern Shanxi and Shaanxi Provinces to use "micro spray" irrigation to improve wheat yields.

As the winter wheat harvest kicks off this month China's wheat market is overshadowed by depressed prices that reflect weakness in China's overall economy. Chinese authorities seem more concerned that the low level of grain prices this year could stir up rural unrest. News articles ahead of the wheat harvest have assured farmers that warehouses have plenty of money to buy the summer's grain crops and plenty of space to store them.

Back in April--before the drought became a major concern--China's Grain and Oils News described China's market for wheat as "loose," characterized by "relatively low" prices. They cited weak demand for flour, minimal use of wheat in animal feed, and an increase in wheat reserves released by local and central authorities as they sold off old stocks ahead of the harvest. With tensions over U.S. tariffs bubbling up in April some Chinese traders and farmers were holding on to stocks of wheat with speculative motives, but the trade war was not expected to have much impact on China's wheat market since it is not reliant on imports of U.S. wheat.

Raw material price data reported by China's National Bureau of Statistics show wheat prices a year ago in May 2024 were close to RMB 2,600 per metric ton, then dropped below 2,450 after last year's harvest in June, and reached a low point below RMB 2,360 in January and February of 2025. Since April wheat prices have rebounded slightly to RMB 2,434 in mid-May 2025, but are still below year-earlier prices. For reference, China's corn price also crashed after last fall's corn harvest, but the rebound in corn prices since January has been stronger than the wheat market's microscopic rebound.

|

| Data from China National Bureau of Statistics raw material prices paid by enterprises. |

The price of flour--the main product of wheat--has shown a similar declining pattern over the past year. Flour prices reported by the food reserve administration have been flat since mid-April despite trade war and drought news. The flour price is now about 10 percent below year-earlier prices.

|

| Data from China's Food and Commodity Reserve Administration wholesale prices. |

An analyst might look at futures prices to discern market participants' expectations, but wheat futures contracts listed on China's Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange have zero trading volume over the past year.

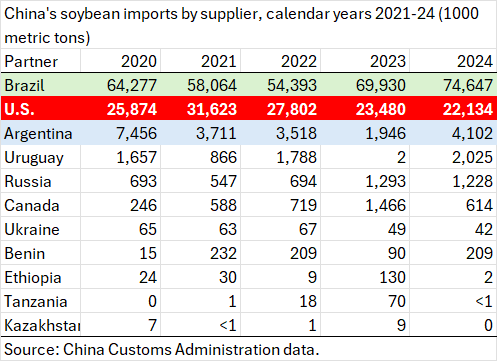

Over the past year China has cut back its wheat imports from all countries, presumably to limit supply and goose Chinese wheat prices upward. During the 2023/24 market year China had imported 13.155 million metric tons of wheat. During the first 10 months of the 2024/25 market year China has imported 2.8 million metric tons. Imports were rock-bottom during October 2024 to March 2025, then bounced to 740,000 metric tons in April. If the drought has no impact on the market and imports revert to low levels in May and June, China's 2024/25 market year imports could come in at about 3 million metric tons--about 10 million metric tons less than the previous year. But if supplies are tight again, and imports continue at the April pace during May and June, its 2024/25 import total could reach 4.3 million metric tons. Either number would be a big drop from China's 2023/24 import total of 13.155 million metric tons. For reference, USDA forecasts 3.3 million metric tons of Chinese wheat imports for 2024/25.

|

Monthly imports during July-June international wheat marketing years.

Data from China Customs Administration web site. |

China's wheat imports respond to market conditions with a long lag that makes it hard to correlate imports with crop conditions, so it could be many months or years--if ever--before we can discern the state of China's 2025 wheat crop.

In an earlier example, China's statisticians proclaimed a record wheat harvest of 13.77 million metric tons for the 2022/23 market year. Leading up to that crop the agriculture minister had raised alarm about the unusually poor state of wheat seedlings, zero-covid lockdowns had impeded access to wheat fields during the spring, and some wheat fields were cut for animal feed or burned due to the crop's poor quality. Despite statistics showing a record crop during 2022 Chinese wheat prices spiked to record levels that year and China's wheat imports soared to over 13 million metric tons. That was the largest amount of wheat imported since 1991/92, and it made China the world's top wheat importer that year. China's price spike during 2022 might have been attributed to the spike in global prices that year due to the Ukraine invasion and closure of Black Sea shipping (even though China does not import Ukrainian wheat), but the surge in Chinese wheat imports when global wheat prices went up only makes sense if China's wheat supply was worse than authorities let on.

So, it's possible that impact of drought on China's wheat crop could be undetected until we see what happens to prices and imports later in 2025. By that time other things will have happened that will obscure the link between crop conditions and market supply and demand.