This year 1,230 Chinese companies applied to import corn, including the world's biggest feed-milling and swine-producing companies. Starch and ethanol producers that were subsidized in past years to sop up excess corn are now clamoring to import corn as well.

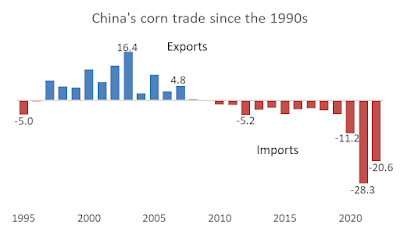

China flipped from corn exporter to importer in a short space of time. Twenty years ago China exported 16.5 million tons of corn, but in 2022 China imported 20.5 million tons and will probably import a similar quantity this year.

|

Note: Calendar years. Source: China customs statistics. |

Clues about China's soaring demand for corn can be gleaned from a list of applicants for the tariff rate quota (TRQ) that allows up to 7.2 million tons of corn to be imported at a 1-percent tariff each year. Imports outside the TRQ system are charged a deal-breaking 65 percent tariff. Prospective importers have to apply every September for a share of the following year's quota.

Chinese authorities grudgingly agreed to publicly release the list of applicants each year as a baby step toward transparency. The list shows the companies that applied, their addresses, products and production capacity. They don't reveal how much quota applicants requested nor which applicants are awarded quota because Chinese officials insist this would be an invasion of privacy.

The chairman of Tongwei Feeds complained at last year's National Peoples Congress that the 7.2-million-ton quota is not nearly big enough to meet the needs of big feed companies. Indeed, corn imports have exceeded the quota by a wide margin each of the last three years. Apparently, some companies are being allowed to import beyond the quota without being charged the 65 percent tariff for out-of-quota purchases.

Nevertheless, the quota seems to be valuable since the number of applicants for corn quota grew by 75 percent between 2020 and 2023--an indication of growing demand for corn imports. The cotton TRQ used to attract the most applicants, but the number of applicants for cotton quota has fallen by half since six years ago. The 1,230 applicants for this year's corn TRQ exceeds the number of applicants for wheat, rice, or sugar TRQs as well.

|

| Source: Tariff rate quota applicant lists posted by National Development and Reform Commission. |

The applicants for corn import quota said they had a total of 378 million tons of corn processing capacity. This exceeds USDA's estimated 297 million-ton domestic consumption of corn in China and the Chinese agriculture ministry's 290 million-ton estimate. Of course capacity exceeds actual use and reported capacity may be exaggerated, but the large capacity number reported by quota applicants suggests potential to use a lot of imported corn and indicates that just about every major corn-user applies for permission to import.

Over 90% of the applicants said they produced animal feed or livestock. Companies whose main product was feed said they had 332.8 million tons of capacity.

More interestingly, there were also applications to import corn from dozens of producers of industrial corn products such as starch, citric acid, ethanol, sweeteners, and monosodium glutamate. Many of these companies received subsidies to process domestic corn during past years of corn gluts--most recently about 4 years ago. Now these companies are looking to import corn:

- 6 fuel ethanol manufacturing plants belonging to state-owned companies COFCO and SDIC. One ethanol plant constructed in Guangxi Province 15 years ago--hailed as a producer of ethanol from cassava that would not compete for grain--applied to import corn and reported that it has 700,000 tons of corn processing capacity.

- 2 manufacturers of DDGS (distillers dried grains with solubles)--China just renewed its "anti-dumping and countervailing duties" on imported DDGS from the United States to protect these producers from imports yet these manufacturers (and the ethanol manufacturers who also produce DDGS as a by-product) are clamoring to import corn as a raw material. Part of China's rationale for singling out U.S. DDGS for exorbitant tariffs is that U.S. subsidies make its corn artificially cheap, yet China is ramping up imports of Brazilian corn which is cheaper than U.S. corn.

- 5 branches of two companies that manufacture amino acids such as lysine and threonine. Note that Chinese officials are pushing an initiative to reduce soybean imports by expanding use of these synthesized amino acids in swine and chicken feed, but these manufacturers use 3.9 million tons of corn as their raw material. Thus, China will likely have to import more corn to achieve their amino acid plan.

- Applicants for corn import quota included 2 branches of the Fufeng Group that produce amino acids and monosodium glutamate. Fufeng's plans to construct a corn-milling plant to produce amino acids in North Dakota have been cited repeatedly by U.S. politicians and news media as evidence of a sinister Chinese plan to buy up American farmland.

Syngenta, a Swiss seed and farm chemical manufacturer owned by China's state-owned chemical behemoth also requested corn import quota, as did premier Chinese seed manufacturer DBN (which is also a massive feed and pig manufacturer).

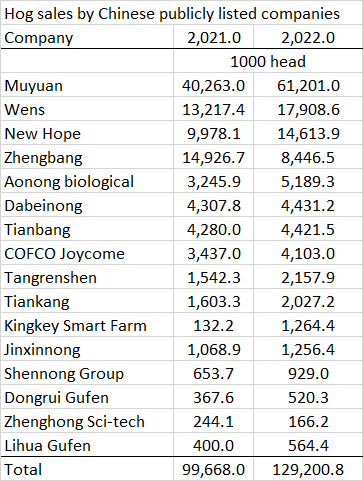

|

| Source: compiled from National Development and Reform Commission list. |

- New Hope and Liuhe--a giant feed, swine and chicken producer--had 76 applicants with a combined 17.3 million tons processing capacity. New Hope Group was ranked no. 2 in the Alltech survey with a reported 28 million tons of production.

- COFCO's headquarters said its company's capacity was 9.5 million tons of corn. Twenty-nine of its individual plants producing feed, ethanol, starch and MSG applied for quota and reported a combined 8 million tons of capacity.

- Twins feed had 74 applicants with 16.9 million tons of capacity. Alltech ranked Twins no. 7 with 11 million tons of production.

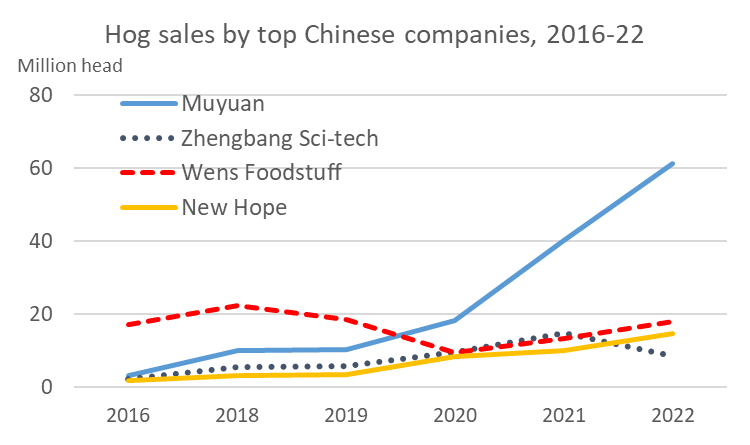

- Wens Foodstuff, a leading poultry and swine integrator that supplies feed to contracting farmers, had 56 applicants and 11 million tons of capacity.

- Haid Feeds had 54 applicants with 13 million tons of capacity. Haid was ranked no. 3 by Alltech with 19.7 million tons of output.

- Muyuan Foods, the biggest swine producer in the world, had 42 applicants with 12.8 million tons of capacity.

- The Tongwei company--whose CEO complained about the TRQ last year--had 18 applicants for TRQ with 3.5 million tons of capacity.

|

| Compiled from National Development and Reform Commission list. |

China's demand for imported corn would be even larger if the high cost of corn were not pushing the price of final products so high that imports of meat are rising. This same process curbed demand for cotton imports--also restricted by a TRQ--by inducing Chinese textile companies to switch to importing cotton yarn which has no quota.

.jpg)