China is on the verge of allowing imports of Brazilian corn. Many observers think China-Brazil negotiations were pushed along by China's expectation of disrupted corn supplies due to the war in Ukraine. If so, the move illustrates China's hijacking of scientific negotiations on pest and plant disease risks for economic and political purposes, the kind of behavior that an earlier generation of trade negotiators tried to stamp out when they set up the WTO trading system.

"It was a strategic consideration by the State to diversify import origins," an anonymous China-based trader told Reuters.

A commentary by Chinese market analysis group Mysteel attributed the Brazilian corn agreement to the risk that a relatively "stable" corn import pattern could be disrupted by the war in Ukraine.

What they meant is that Chinese authorities face the prospect of having to import nearly all their corn from the United States if Ukrainian corn supplies are disrupted. Authorities are scrambling to line up alternative suppliers to avoid being at the mercy of American corn exporters.

Eight years ago the Dim Sums blog recounted a similar situation when Chinese authorities became desperate to diversify corn suppliers after China's corn imports soared to 5.5 million metric tons in 2012--and 98 percent of the imports were supplied by the United States. During 2012-13 China rushed through agreements to import corn from Argentina, Brazil and Ukraine, but none of the agreements resulted in much trade until Ukrainian shipments ramped up in 2014.

An opaque GMO approval process is another lever China uses to slow imports depending on domestic market conditions. 2014 was the same year Chinese authorities rejected nearly every U.S. corn shipment because they said they discovered an unapproved GMO variety inspectors had been ignoring for years as the seed company's application hung in the limbo of China's GMO approval system.

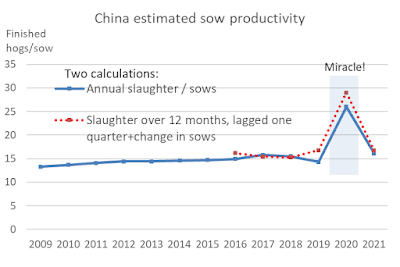

A recent commentary by China's BRICS market analysis group observed that no significant trade ever occurred after China and Brazil signed the initial 2014 protocol to admit Brazilian corn to China. BRICS explained that China's agriculture ministry had not approved the many GMO corn varieties grown in Brazil, so only a few shipments of Brazilian corn had been made. The BRICS commentary attributed lack of movement on negotiations with Brazil over the last 8 years to China's huge corn glut that appeared in 2015 and a multi-year program to disgorge massive Chinese corn reserves that was completed in 2020.

BRICS explained that China is now eager to push ahead on opening the market to Brazilian corn because the corn reserves have been depleted, China's corn needs have grown, and the country has a 50-million-ton feed grain deficit. BRICS explained further that China opened its market to Brazilian corn and other commodities due to the Russia-Ukraine war and tensions with the United States.

The Mysteel commentary pointed to approval of GMO corn varieties by China's agriculture ministry as the key chokepoint in actually opening trade.

A Brazilian source told Channelnewsasia.com that a biotechnology equivalence agreement related to corn is still required and he suggested that China's approval of biotechnologies "needs to be more agile."

China's new agreement with Brazil seems to be part of a larger initiative to expand agricultural trade with that country. Brazil already supplied 22 percent of China's agricultural imports in 2021, far more than any other country. Authorities said they also reached agreements on soybean meal and peanuts and are making progress on protocols for soy protein, orange fiber granules from Brazil and Chinese pears. However, the timing of the corn announcement suggests that market developments have motivated Chinese officials to move the negotiations forward.

The architects of WTO trading rules for agricultural commodities envisioned "science- and risk-based" determination of standards, inspection and quarantine practices, and approvals of plant varieties, hormones, etc. to stop the use of such measures as protectionist trade barriers. China claims to support these principles but their authorities clearly view them as valves to turn on and off the flow of agricultural imports and exports.

A 2011 paper by an agriculture ministry international trade policy advisor on maintaining "agricultural industry security" called for fully utilizing border measures, including plant and animal inspection and quarantine rules to protect the country's small-scale producers. The paper also calls for using animal and plant inspection and quarantine, tariffs and tariff-rate quotas, and technical measures.