A meeting of Chinese soybean scientists in 2019 concluded that the country's soybean industry's output was small, yields were low, and the processing sector was weak.

Despite the ideas offered by the scientists for boosting domestic production, China's imports of soybeans during 2021 cost RMB345.9 billion ($53.6 bil), up 26.1% from the previous year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics communique on 2021 economic data. China's imports of edible oils cost an additional RMB 70.6 billion yuan ($10.9 bil), up 24%. Soybeans were one of the top-valued import commodities, exceeded only by petroleum, iron ore, electronic components, plastic, and natural gas.

The increase in import cost reflected a boost in prices. The volume of soybean imports was down 3.8 percent and the volume of edible oil imports was down 3.7 percent in 2021. With the value increasing 25 percent or more and volume shrinking less than 4 percent, China's demand seems relatively insensitive to price increases.

Imports of oilseeds in January-February 2022 totaled 13.9 million metric tons, up 4.1 percent from a year earlier.

The growing cost of grease-related imports got the attention of Chinese leaders. Another of a series of soybean revitalization programs was announced last year. An initiative to replace imported corn and soybean meal in animal feed was announced in April 2021. The central leadership's "Document Number One" on rural policy released in February 2022 featured a project to increase soybean and oilseed production capacity that included "rotation subsidies" for soybeans, transfer payments to oilseed-producing counties, conversion of rice paddies to soybeans in parts of Heilongjiang where groundwater is depleted, a plan to intercrop soybeans with corn in alternating rows, and plans to plant rapeseed on fallow land in the Yangtze River valley and a pilot to plant soybeans on saline soil.

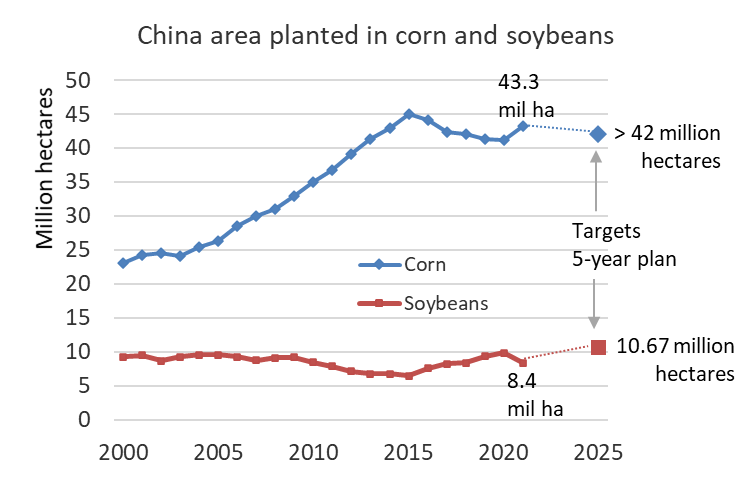

A 16-percent decline in China's soybean production last year set off alarm bells in Beijing. Agricultural officials had already set targets for reviving soybean acreage, and the latest 5-year plan called for a modest increase in soybean planting to 10.67 million hectares by 2025. The plan had apparently been drawn up before statistics revealed that area planted in soybeans plunged to 8.4 million hectares in 2021. The plan also called for corn acreage to be at least 42 million hectares in 2025--also before statistics revealed a surge in corn area to 43.5 million hectares last year. Corn and soybean planting data tend to be mirror images of each other since the two crops are planted in similar geographic regions, so increasing production of both crops is not realistic.

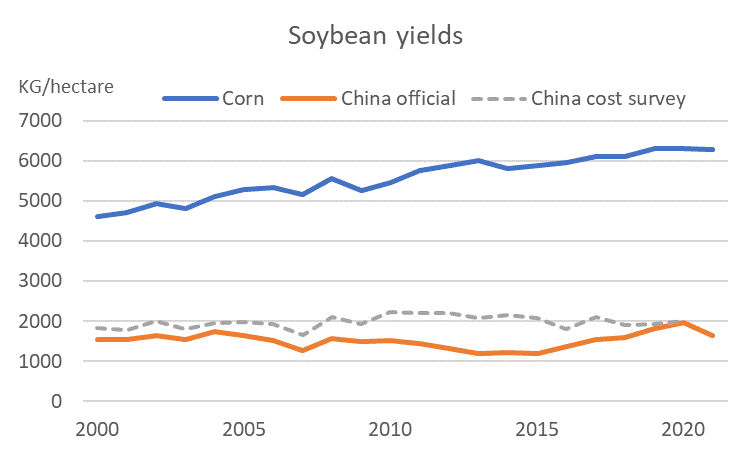

The fundamental problem is that soybean yields are low and falling behind yields of fertilizer-juiced crops like corn. China's corn yield is more than three times the average soybean yield. With soybean yields mostly stagnant while corn yields grow, soybean prices have to go up in order to keep soybeans profitable for farmers. |

| Official yields from China's National Bureau of Statistics; cost of production yields from China National Development and Reform Commission. |

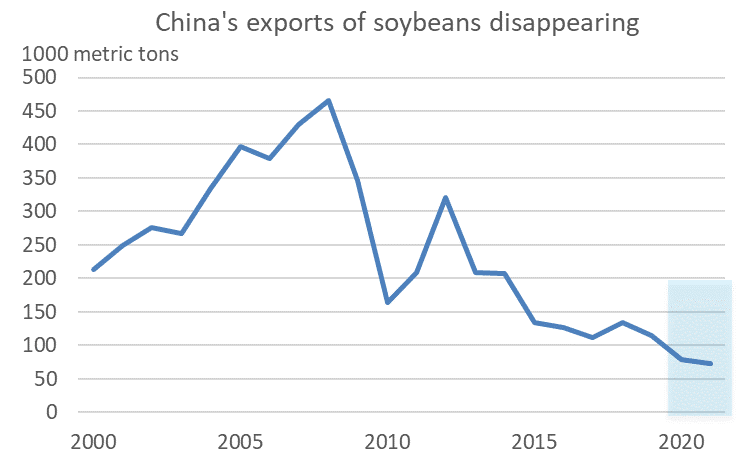

The strategy worked for a while. China's exports of soybeans peaked at over 450,000 metric tons in 2008. (Interestingly, this peak in exports coincided with the spike in use of melamine to mask the absence of protein in feed and milk during the global food price spike in 2007-08.) Since then, China's use of domestic soybeans for crushing became vanishingly small, China's exports of soybeans atrophied, and the country began to import non-GMO soybeans from Russia. The long-term collapse in China's soybean exports to under 80,000 metric tons in 2020 and 2021 signals growing demand at home and perhaps tighter supplies of domestic soybeans than China's statisticians have acknowledged.

|

| China's customs data. |

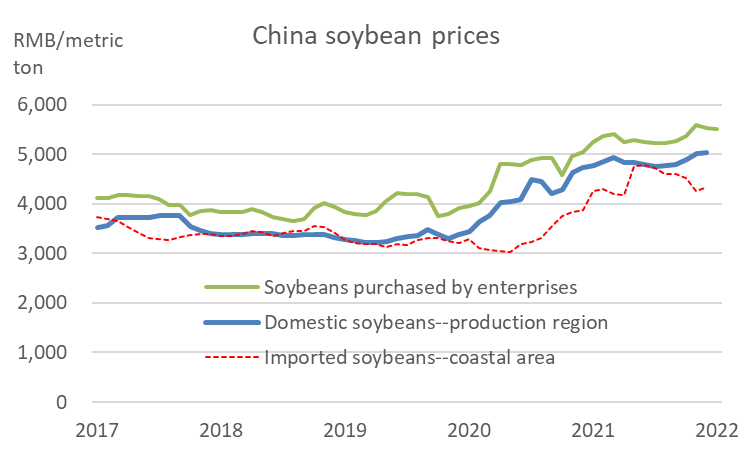

The scarcity of China's non-GMO soybeans was exacerbated in 2019-20 after storms hit Heilongjiang Province--China's largest soybean-producing area--during the fall 2019 harvest, cutting production by 25-30 percent. A shortage of domestic non-GMO soybeans drove domestic bean prices sharply higher during 2020. Prices rose a bit further after the 2020 harvest and are up again after the fall 2021 harvest. The premium for domestic Chinese soybean prices over imported soybeans remains wide by historical standards--indicating tight supplies of non-GMO soybeans.

|

| Domestic and imported prices reported by China National Grain and Oils Information Center; purchases by enterprises reported by National Bureau of Statistics. |

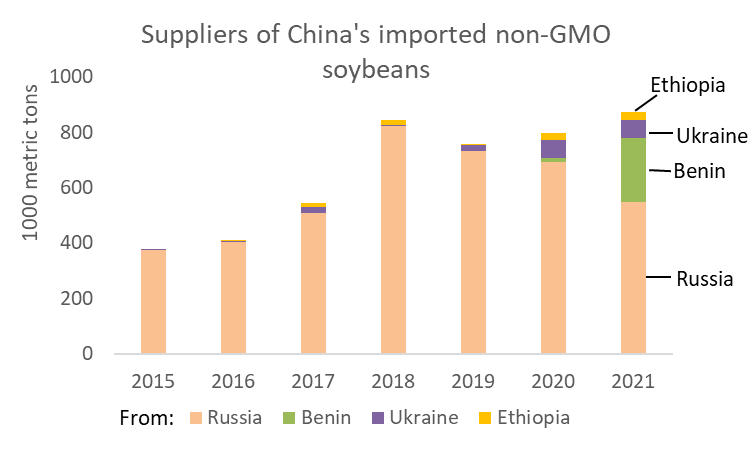

Another indicator of tightening supplies is China's rising imports of non-GMO soybeans from Russia. Imports peaked at 823,000 metric tons in 2018. Industry sources say that 25-30 percent of the soybeans produced in Russia's Far East are grown by Chinese companies and farmers. Most of these beans are brought into China by truck. As supplies became tight, some food companies in Shanghai and Jiangsu began importing Russian soybeans by ocean-going vessels.

Beginning in 2020, covid restrictions disrupted the Russia-China soybean trade. Then Russia imposed an export tax on soybeans in 2021 that further curtailed the trade. China's soybean imports from Russia during October-December 2021 were less than 100,000 metric tons, down from 250,000 metric tons during those months two years earlier in 2019. China has been trying to diversify its soybean suppliers by importing from Ukraine, Africa and Kazakhstan, but Benin is the only one supplying significant volumes. Tanzania was approved last year.

|

| Chinese customs data; calendar year data. |

Meanwhile, after much discussion of import diversification, Brazil supplied 60 percent of China's overall soybean imports in 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment