China's ban on 5 U.S. agricultural exporters contrasts with its lenient approach to domestic product safety and to suppliers in favored countries. This highlights China's cynical use of plant and animal quarantine and food safety inspections as a tool to control the flow of imports and to "diversify" import sources.

On April 4 China's customs administration suspended 4 U.S. suppliers of sorghum and meat and bone meal and 2 suppliers of poultry products (one company appears to be on both lists):

- Chinese customs said they detected levels of zearalenone--a mycotoxin produced by certain types of mold--in the sorghum supplier's shipments.

- Chinese customs said they detected salmonella in shipments by 3 companies of meat and bone meal to be used in animal feed.

- Chinese customs said they detected furazolidinone, a drug banned in China, in three batches of chicken products supplied by 2 U.S. poultry producers.

A Customs administrator cited Chinese laws and regulations violated by the shipments and claimed that they threatened the safety of food in China, thus giving the suspensions an appearance of conformity to WTO requirements that such actions should be based on science and published regulations. In practice, China's inspectors of agricultural and food items are selective about which products they reject and the suppliers they suspend. Despite the pretense of science and rule-based enforcement, food inspections in China are used as a policy tool that discriminates against enemies and favors allies.

Below are some examples of problematic products that China did not ban or suspend.

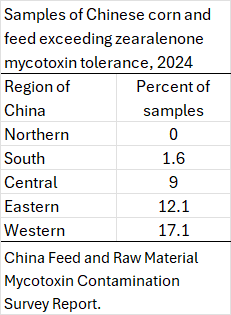

While the suspension of the U.S. sorghum supplier suggests China has great concern about the safety of its grain supplies,

a report on testing of 654 corn samples from domestic Chinese corn and feed products revealed that zearalenone contamination exceeded standards in 17.1% of samples in western China, 12.1% in eastern China, and 9% in central China. According to the report, zearalenone contamination was more serious than contamination by other mycotoxins also detected in Chinese corn. China's grain reserves surely contain a significant percentage of moldy grain, but no public reports on test results are ever revealed to the public.

China's customs administration website

posts monthly lists of imported food shipments it has rejected (in Chinese only). None of the suspended U.S. companies appeared on these lists. On the other hand, monthly rejection lists reveal that shipments of some overseas suppliers are rejected over and over, apparently without prompting suspensions.

The most prominent and puzzling example is shrimp imported from Ecuador. The Ecuadorian shrimp stand out from other rejections because of the large volume of shipments (hundreds of metric tons) and their consistency (rejections appear nearly every month for 5 years). Rejections of Ecuadorian shrimp began to show up regularly in 2019, attributed to detection of fish diseases.

Ecuadorian shrimp briefly hit the news in July 2020 when Chinese authorities claimed to find covid-19 virus on containers and packaging, and three Ecuadorian exporters were temporarily suspended. During 2020 China was trying to promote its claim that covid-19 entered China on contaminated food shipments. Customs rejections still listed "animal disease" as the reason for rejection for nearly every shipment.

|

| Compiled from China Customs Administration reports. |

Over the last 5 years customs reports have listed 55 companies supplying the rejected Ecuadorian shrimp. One company has had over 100 shipments rejected (it was suspended in July 2020 but began appearing on rejection lists again in 2021). Another company had over 50 rejections. There were no announcements of suspended companies except in July 2020. In recent months a couple of shrimp shipments were rejected for detection of a type of nitrofurans drug--related to the furazolidone drug blamed for rejection of U.S. poultry shipments.

Rejections of Ecuadorian shrimp finally tailed off in 2023 and early 2024. Then, in early 2024 Chinese

news media instigated a scandal over sulphur dioxide contamination of Ecuadorian shrimp served in the Hangzhou restaurant of a Chinese internet celebrity--the first time the shrimp had received publicity since 2020. A month later, an importer claimed that accusations were false because it had been inspected at the border, but

an "anti-counterfeiter" had the shrimp tested and confirmed that sulfur dioxide levels were 7 times the national standard due to use of sodium metabisulfite to prevent decomposition and keep the shrimp white. Two months later customs rejections of Ecuadorian shrimp spiked to their highest-ever level, this time predominantly citing excessive levels of sodium metabisulfite as the problem. Customs officials apparently resumed their rejections when the shrimp came to the public's attention. Ecuadorian shrimp are still being rejected in 2025, but just a handful of shipments per month.

China's tolerance for rotten post-Soviet chicken is another puzzling phenomenon. After

China approved imports of Russian chicken in 2019 China's customs lists have consistently reported rejections of chicken shipments from Russia and Belarus during most months. There were brief gaps in early 2021 and early 2024, but most other months had rejections of Russian or Belarussian chicken. The rejections were predominantly based on visual inspections (which usually means the product is spoiled or filthy). Rejections came from dozens of suppliers with a confusing mix of post-Soviet-style company names. One Belarussian company had over 50 rejections and a Russian company had 19, but most had less than 10 rejections. With a 5-year history of problems, why didn't China suspend Russian or Belarussian exporters or place blanket ban(s) on chicken from these countries?

|

| Compiled from China Customs Administration reports. |

These examples contrast China's apparent tolerance for some problematic products that are rejected month after month against the suspensions of U.S. exporters last week after 1 or 2 problematic shipments (although they have not been included on the list of rejections). These comparisons call into question China's claim that its border inspectors use a consistent risk-based approach. While China claims to be an exemplar of a science- and rules-based trading system, its officials appear to use inspections and suspensions as a discretionary tool to reward or punish suppliers.

1 comment:

Nearly all feed companies using U.S. sorghum in China are well aware of the potential for zearalenone in U.S. sorghum, which can occur but not prevalent, and they test it and blend it accordingly. They use sorghum sparingly in swine rations, where it is a problem, but more liberally in poultry rations (ducks and chickens) where zearalenone does not affect feed conversion (sorghum also has to be more precisely milled for swine, but not for poultry). Because of the issues with toxins in China's own corn supplies, outlined in this post, most modern feed companies in China (the ones that use imports) are adept at testing and adjusting their feed ingredients.

Because of this, I imagine the companies that contracted for the U.S. sorghum that China's authorities rejected, ostensibly to protect them, are not happy about this and are scrambling to find supplies to replace them.

Post a Comment